Cervical screening is an important and potentially life-saving procedure, but at the moment 1 in 3 women in the UK feel unable to attend them. This is huge issue for women’s health and we should be promoting uptake as well as adapting medical procedures to make them more accessible. However, all too often campaigns promoting access to this service fail to understand and address the real reasons behind a lack of attendance.

For many women, cervical screening is an overwhelming prospect. This is especially true for women who have experienced sexual violence, where the physical invasiveness and lack of control can trigger painful memories and where traumatic experiences can be relived. This is not a niche issue; we live in a country where most women have experienced some form of sexual violence and where 85000 women are raped every single year. 1 in 3 women will be raped or beaten in her lifetime. Incidentally that’s the same proportion that currently avoid their smear test.

Conventional campaigns that encourage women to go for these invasive physical examinations must therefore cater for these women too. However, rather than pursuing inclusive tones, many campaigns chose an accusative narrative that stigmatises women who– for reasons of fear or the simple inability to access such services or end upon waiting lists – do not receive this fundamental health check that everybody with a cervix should have access to.

To illustrate the ways in which this plays out, I’ve picked a variety of promotional material from the past year.

One headline from the NHS read “1 in 3 women aged 25-29 fail to attend cervical screening.” This sentiment places responsibility for accessing smear tests solely on young women and tells them they have ‘failed’ if they’ve not yet managed one. It disregards the multiple and complex acts of violence women are exposed to, not to mention the abysmal care many survivors of sexual violence have received from medical professionals. We should be listening and responding to stories from people like this courageous woman:

“My mother died of ovarian cancer when I was 12 and the year after, I was raped. My doctor told me that if I didn’t have a successful smear he would take me off his list otherwise it would appear as negligence on his part. He then struck me off his list for not having a smear test… I couldn’t have one, it’s not because I didn’t try. I tried really hard for a whole decade to have one and I gave up… I felt like a failure and I blamed myself.”

I hope it’s evident why slogans like “you’ll wax your bikini line, but you won’t get a Smear!” (developed through the One-Minute Briefs project where agencies mock up an idea in a minute) feed into reductive stereotypes around women being obsessed with their looks and is offensive and shaming.

Often, fear tactics are adopted to encourage attendance, with one campaign leading with “don’t regret it later”. The slogan is accompanied by a photograph of a women looking ill and without scalp hair, implying she has cancer and is undergoing chemotherapy. Apart from the fact that psychological research into health-related campaigns show that messages based on fear are rarely effective, many women are already aware of the risks associated with not testing. One of the My Body Back Project service users explained to us:

“After I was raped I was often on edge and anxious and when I received my first letter inviting me for a cervical screening I stopped going to the doctor all together. I knew I couldn’t handle a smear test and I knew I wouldn’t be able to explain why. I did worry about having cervical cancer, but I remember feeling that I could probably handle death easier than a smear test, so I was left without any health provision at all.”

If we want to support women in accessing cervical screening we need to be clear about the responsibilities of health services to make the procedure as safe as possible. Supporting women should be about opening up choices and possibilities, not closing them down.

One of the key take home messages of these campaigns is that a smear test is not a big deal, but “straightforward and over within minutes.” The implication is that women who are worried about smear tests are overreacting.

The reality is that for many women smear tests can be re-traumatising. The thought of having to disclose their experience, of being touched and of feeling out of control over what is happening to their bodies results in an experience that has the potential to be very high risk.

When we minimise rather than attempt to understand women’s concerns, we silence them. Instead of listening to women and the reasons for their choices, campaigns like this ultimately infantilise them.

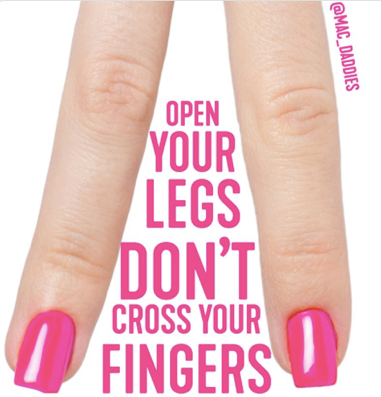

Many women we’ve spoken to at the My Body Back Project are concerned that the doctor will repeat language their abuser used. Phrases like “if you weren’t so tense it would be over faster” can trigger memories of abuse. Thus, violent messages such as the phrase “open your legs don’t cross your fingers” as used in the advert from The Mac Daddies Creative Collective, perpetuates the perception that women should do what they are told, regardless of how they feel about it. In any other context, this in itself would be understood as an act of violence.

Of course, awareness-raising is of utmost importance, but not when it boils down to victim blaming. These slogans – while meant well – are a symptom of how we as a society view women and value their care. From the perspective of the My Body Back Project and our experience with our clients, the lack of uptake of smear tests is not a failing of women, but a failing of the NHS. Campaigns which place full responsibility on women, don’t respond to the underlying reasons, and most importantly don’t make the accessibility of smear tests in a safe and comfortable environment any easier, fail to deliver to half of the population.

I call for a wider understanding of the complex barriers many people face in accessing the healthcare they deserve and for MPs and medical practitioners to take this issue seriously. This is not about women being inconsiderate or sloppy, but about the healthcare system not catering to the needs of some of the most vulnerable groups in our society.

Ellie is a Lecturer in Urban Innovation at UCL and the Chair of the trustee board of the My Body Back Project, a charity with supports people who have experienced sexual violence in accessing the health services they need. They do this by running specialist services, including a cervical screening clinic and maternity clinic designed especially for women who have experienced sexual violence. Both of these clinics work very sensitively with women, so they feel safe, relaxed, and their individual needs are met. They also run Café V, which is a quarterly session for women to learn about loving their bodies after violence. These run on a Saturday morning, and are a safe space for those who attend to talk about enjoying sex again – by themselves or with a partner – and any problems they may be experiencing. They do this with lots of tea and cakes on standby, and in a cosy atmosphere.